Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), the nineteenth-century German historian, is generally considered as the Father or Columbus of modern history and the Father of modern scientific history. He is also known as the founding father of Empirical historiography and he stood for objectivity. It was Ranke who must be credited with the beginning of modern historiography.

Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), the nineteenth-century German historian, is generally considered as the Father or Columbus of modern history and the Father of modern scientific history. He is also known as the founding father of Empirical historiography and he stood for objectivity. It was Ranke who must be credited with the beginning of modern historiography. Blog for students interested in the History of History and its Practices

Sunday, 13 August 2017

Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), the nineteenth-century German historian, is generally considered as the Father or Columbus of modern history and the Father of modern scientific history. He is also known as the founding father of Empirical historiography and he stood for objectivity. It was Ranke who must be credited with the beginning of modern historiography.

Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886), the nineteenth-century German historian, is generally considered as the Father or Columbus of modern history and the Father of modern scientific history. He is also known as the founding father of Empirical historiography and he stood for objectivity. It was Ranke who must be credited with the beginning of modern historiography. Auguste Comte and Positivism

Auguste Comte (1798-1857) was the French positivist philosopher. His full name was Isidore Auguste Marie Francois Xavier Comte. The aim of positivist philosophy was to liberate history from the hold of religion and metaphysics, and to make history to stand on its own base of historical laws. Comte wanted to introduce the scientific observations into the study of history

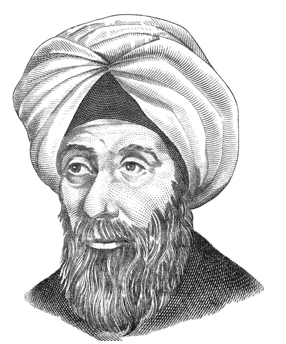

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (AD 1332-1406), is the most celebrated historian of the medieval period, belonging to the Arab historiography. He is well-known for his work Universal History.

St. Augustine and Christian Historiography

St. Augustine (AD 354-430), the Bishop of Hippo in North Africa was the greatest Church historiographer of the medieval period. He is well known for his work City of God and for his providential philosophy of history.

Friday, 11 August 2017

Postmodern Challenge on History

- The critiques have pointed out that in some extreme forms of postmodern relativism, the implication may be that ‘anything goes’.

- Moreover, the postmodern analysis of society and culture is lop-sided because it emphasises the tendencies towards fragmentation while completely ignoring the equally important movements towards synthesisation and the broader organisation.

- It also tends to ignore the roles of state and capital as much more potent tools of domination and repression.

- Some critics also charge postmodernism with being historicist as it accepts the inevitability of the present and its supposedly postmodernist character. If the world is now postmodern, it is our fate to be living in it. But such postmodernity that the western world has created now is no more positive than the earlier social formation it is supposed to have superseded.

- Moreover, it is not very sure whether modernity has actually come to an end. In fact, large parts of the world in the erstwhile colonial and semi-colonial societies and East European countries are now busy modernizing themselves. The concept of postmodernity, therefore, remains mostly at an academic and intellectual level.

- Critics also argue that many postmodernists, deriving from poststructuralism, deny the possibility of knowing facts and reality. As a result, no event can be given any weightage over another. All happenings in the past are of the same value.

Hypothesis

A hypothesis is generally considered a research indicator. It is a tentative explanation of the research problem

or a guess about the research outcome. The hypothesis is usually considered the principal instrument in

research. It helps social scientists to suggest a theory that may

explain and predict the events. The hypothesis is like a formal research question intends to resolve. The

hypotheses in historical research are useful in explaining events, conditions, or phenomena of the period in question. Hypotheses are particularly necessary

for studies where cause and effect relationships are to be discovered. The

hypotheses for historical research may not be formal hypotheses to be tested.

They are written as explicit statements that tentatively explain the occurrence

of events and conditions. According to Borg, without hypotheses, historical

research often becomes little more than an aimless gathering of facts.

Functions or Importance of Hypotheses

- Provides a clear focus to research

- Helps in selecting and collecting relevant facts

- Helps to explain the research problem

- Offers a temporary answer to the research question

- Provides a structure and operational directions to research

- Helps to suggest a theory that may explain and predict events

- Provides the framework for drawing conclusions

- Explanatory hypothesis – this is especially used in finding outlaws or formulas acting in history

- Descriptive hypothesis – this is used for making a complex mass of facts, that are isolated from one another

After

an extensive literature survey, the researcher should state in clear terms the

working hypothesis or hypotheses. A working hypothesis can be framed through:

a) Review of similar studies in the area or of the studies on similar problems

b) Examination of available data and records

c) Discussions with colleagues and experts about the problem

d) Preliminary personal investigation of the research problem

Working hypotheses are more useful when stated in precise and clearly defined terms. Hypotheses act as a step toward research work. Thus, working hypotheses arise as a result of pre-thinking about the subject.

A hypothesis must possess the following characteristics:

- It should be clear and precise. If the hypothesis is not clear and precise, the inferences drawn on its basis cannot be taken as reliable.

- It should be limited in scope and must be specific. No vague terms should be used in the formulation of a hypothesis.

- It should be stated as far as possible in the most simple terms so that the same is easily understandable by all concerned.

- It should be consistent with the most known facts. It should not conflict with any law of nature which is known to be true.

- It should be empirically testable. It should be capable of being tested whether it is right or wrong.

- It should be conceptually clear. The concepts used in the hypothesis should be clearly defined

- It should describe one issue only. It can be framed either in descriptive or relational form.

- It should be related to available techniques and methods.

- It should not be contradictory.

It is generally considered that at the end of

the research, the researcher should test the hypothesis. A hypothesis, when

empirically proved, helps us in testing an existing theory. This should be done

with the empirical evidences analyzed and interpreted during the research. This

testing of the hypothesis allows the researcher to verify existing knowledge,

fact, or theory as to right or wrong. In other words, when a hypothesis is tested,

it aimed to support or reject an existing theory or facts. It also explains

the empirical conditions in which the theory is accepted or rejected. Each time

a hypothesis is tested empirically, it tells us something about the phenomenon

it is associated with. If the hypothesis is empirically supported, then our

information about the phenomenon increases. Even if the hypothesis is refuted,

the test tells us something about the phenomenon we did not know before. A

hypothesis, after its testing, may highlight the positive and negative aspects

of the existing social or legislative policy. In such a situation, the tested

hypothesis helps us in formulating (or reformulating) a social policy. It may

also suggest or hint at probable solutions to the existing social problem(s)

and their implementation.

Appendix

- supporting evidence (preferably a copy of the primary documents like orders, letters, etc.)

- technical figures, graphs, tables, statistics

- a detailed description of research instruments

- maps, charts, photographs, drawings

- questionnaires/surveys

- transcripts of interviews

- The appendix helps the researcher to display the relevant original source materials used for the study

- The appendix can provide additional information regarding the study

- Too lengthy information can be given in the appendix without affecting the main body of the text

- The researcher can give supporting documents in the appendix for validating his arguments.

- Can be used when there are constraints placed on the length of your paper.

- Appendices may place at the end of the main body of the text

- Appendices should be arranged sequentially (preferably in Roman numbers) by the order they were first referenced in the text

- Each appendix begins on a new page

- The heading should be "Appendix," followed by a letter or number [e.g., "Appendix A" or "Appendix 1"], centered and written in bold type.

- Appendices must be listed in the table of contents [if used].

- The page number(s) of the appendix/appendices will continue with the numbering from the last page of the text.

Ontology

Ontology is a branch

of philosophy that deals with the nature of existence and the construction of

reality. In another sense, it deals with the nature and structure of “reality”.

It is also considered the fundamental

branch of philosophy that deals with the existence or non-existence of things. Some

of the basic questions in the ontology are:

ü How do we determine if things exist or not?

ü Is everything that exists real?

ü What is the meaning and nature of reality?

ü What is true?

ü What do we think the truth is?

The term Ontology combines two Greek words ‘Onto’, which means existence or being real, and ‘Logia’, which means science or study. Thus, etymologically, ontology means the study of being or existence. Ontology is the study of things that exist, especially things whose existence is logically brought about by a theory (for example the existence of God). Ontology studies the first principle of the essence of all things. Aristotle called it the “first philosophy”.

In more recent analytical philosophy, ontology refers to the study of ‘what is’. Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche and Gilles Deleuze made poplar contributions to the understanding of ontology. Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher and mathematician see ontology as a ‘science of essences’.

The two essential branches of philosophical ontology are Ontological Materialism and Ontological Idealism.

§ Ontological Materialism is the belief that material things are more real than the human mind.

§ Ontological Idealism is the belief that the human mind and consciousness are more real than material things.

Further, there are branches of ontological realism and ontological relativism.

ü Relativists believe in multiple versions of reality shaped by the context. What is real depends on the meaning you attach to the truth. Truth does not exist without meaning. Truth evolves and changes depending on your experiences. Truth is created by meanings and experiences. Thus, it believes in constructionism.

Historical Ontology

Historical ontology concerns the historian’s construction of historical facts or reality. The question is about the conditions of being under which we create the past- as - history. Historian is necessarily an ontological creature who has prejudices, preconceptions, and beliefs about the nature of existence. Historians use several ways to create ‘ontology-free’ historical knowledge. The important approaches are:

(1) The positivist approach – the way of covering laws

(2) The

empiricist-objectivist approach – past is represented through evidence

(3)

Relativist approach – links historical events together to establish realism

(4) The

inductive approach – establishes truth conditions

The outcome is that the reality of the past is accessible, but it is not free from the ontological positions of historians. Frank R. Ankersmit argued that historians write ‘not in epistemological but ontological terms’. Ontology will always get in the way of ‘knowing the past’.